Fallen Angels

Priory Theatre, Kennilworth

****

JUST the

briefest glance at the opening set for

Fallen Angels

gave one the feeling this was going to be a worthwhile evening.

Baby grand piano, sideboard and drinks,

fireplace, curtained window, elegantly arched rear entrance, elegant tea

table, chaise longue, paintings on the wall

(landscapes,

but one looking – from where I sat - like a Modigliani), four varied

plants, appealingly decorative (later elaborated into six), subtly

angled walls with a sort of quasi-Regency wallpaper. (landscapes,

but one looking – from where I sat - like a Modigliani), four varied

plants, appealingly decorative (later elaborated into six), subtly

angled walls with a sort of quasi-Regency wallpaper.

Planning had gone into all this, as it had into

this entire production. Remarkable that all this onstage material left

plenty of room for gallivanting. Set Designers were Nigel Macbeth and

Richard Poynter, Plus additional cheers for the three-man Props team.

Fallen Angels

is perhaps predictable Noël Coward. Husbands fall into a rage about

nothing, the past – or presumed past - comes back to haunt rocky

marriages, the wives – best friends – have tiffs and then tumble into a

major row; the difference between ‘loving’ and ‘being in love’ is

demarcated; and everyone has to put up with the pert, know-all maid, who

mischievously wraps them round her little finger.

There’s not a lot more than that, but Coward puts

his finger on the complete futility of petty arguments and trivial

jealousies, as if to underline their complete pointlessness. What they

do imply, however, is the growing tedium of a marriage after a few

years: the fading of passion (‘It’s so uncomfortable, isn’t it,

passion?’) and the aching for something to replace it, as the two wives

willingly concede given that ‘rampant ecstasy subsides’.

The husbands make their presence briefly felt:

Frederick or Fred (Chris Cortopassi) at the outset and later William

(Ben Wakeling), colourfully kitted out for golf which the two of them

head off for, relieved to be out and about. This leaves the two girls,

Julia (Natasha Lewis) and Jane (Mahalia Carroll) on their own to frolic,

interrupted with increasingly hilarious regularity by Jasmine Saunders

(or ‘Saunders’, played by Teresa Robertson), the maid.

Robertson is new to the Priory, but what a catch

she proved. As Julia awkwardly strums the piano (with a delicious

tentativeness: nice Sound Design from Arthur Marshall, with June Curry

offering Music Tuition – presumably in how to do it haltingly as well as

smoothly) the maid sticks her nose in and goes one – or two – better.

If a song is in French, Saunders knows how to

enunciate that much more artfully. She was, as it happens, ‘in the

desert with the Red Cross’; plus not to mention, when there are drinks

to mix, a barmaid. Critical, judgmental, presumptuously posh-spoken, she

potters around the stage – her own domain, as she sees it - nose turned

up, as hilariously and snootily as Freddie Frinton.

But the bulk of Act I, indeed of the whole play,

falls on the two women, Julia and Jane, played like old school chums

who’ve known each other for ever – and still much given to laughter, confiding, suppressed resentment

and, at the high points, downright, out and out bitchiness.

– and still much given to laughter, confiding, suppressed resentment

and, at the high points, downright, out and out bitchiness.

Two things helped them shoulder such a weighty

amount of text, shifting moods and ear-battering explosions. One was the

costumes (Mike Brooks) - beautifully 1920s (Coward first staged it in

1925), not just elegant for both girls but really rather beautiful, and

changed for Act 2. Why so very successful? The Priory retains its own

wardrobe, clearly full of gems, and has the able hands armed with the

keen intelligence to adapt them where necessary. .

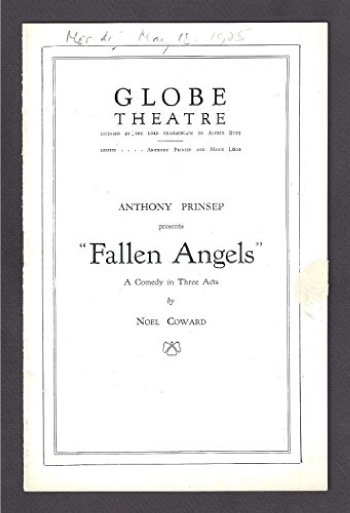

The playbill for the original production in 1925

The other was surely all down to the Director,

Linda Lewis, also mounting her first show for the Priory. The moves,

especially Julia’s in the early stages, but actually the female

characters throughout the evening, even the circling way Saunders pours

the champagne (going the ‘long’ way round) were splendidly mapped,

natural, apt but also creative. And together with Julia’s striding up

and down or Jane’s flouncing, the moves generated the pace, which was

beautifully concocted, so that the whole evening, riddled with snide

Coward humour, never lost its forward momentumNatasha Lewis’s Julia was

something of a revelation. Her facial expressions – eagerness,

determination, disappointment, desperation, exasperation, infuriation –

seemed to unveil an unending flow of shifting moods. She was funny,

edgy, irritable, judgmental, constantly, fretfully on the move, not

least when annoyedly trying to reclaim her territory from the impossible

maid.

Cavorting with Jane like a pair of giggling

schoolgirls (it’s all in the script) or baring her teeth and threatening

to evict her chum when they by stages fall out (‘It’s always the same

when sex comes up; it’s rotten and beastly and it wrecks everything.’)

– that too turned out to be really quite subtly

paced. Lewis gave a treat of a performance, invariably genuinely clever,

and most impressive for both its range and its joyous, nervy,

edge-of-seat unpredictability.

Mahalia Carroll’s Jane

came close to matching Lewis. When they begin to get tipsy, it’s Carroll

who leads the way, making a fine job of getting squiffy and clumsy and

dopy which was actually rather neatly observed. She has some nice

ripostes (Julia: ‘To put it bluntly, we’re both up for a lapse.’ Ja ne:

‘No, dear, it’s a relapse.’

‘Several drinks do no harm. It’s only the first that’s dangerous’); and

pulls off a remarkable bout of coughing and spluttering (from

reluctantly downing Benedictine) that sounded blissfully genuine. ne:

‘No, dear, it’s a relapse.’

‘Several drinks do no harm. It’s only the first that’s dangerous’); and

pulls off a remarkable bout of coughing and spluttering (from

reluctantly downing Benedictine) that sounded blissfully genuine.

The point is, and the cause of their falling out,

all centres round an old flame of both of them, Maurice Duclos. They can

laugh about him and alternately relish and dismiss him, and engage in

endless chatter about him, but the fact is that both clearly fancied him

and have an appetite for the idea of being fancied again.

Edna Best, as Jane, Austin Trevor as Maurice

and Tallulah Bankhead as Julia in the original 1925 London production.

In fact nothing has happened – the chap, who is

expected, hasn’t even turned up yet, though it opens the way to a in the

lot of comedy regarding incoming telephone calls and pointless answering

of the front door.

One of many highlights of this girlie tussle is

when the two get wrapped up in the telephone wire – witty rather than

corny because as they get more enmeshed, in a neat piece of dramatic

irony, neither of them realises what’s happening.

But when the husbands return from the fairway,

they walk straight into this bizarre situation – their wives’ mutual

enthusiasm for someone the existence of whom neither man had any idea –

and ructions follow. The fact that nothing has ‘happened’ – the men fear

the worst – only serves to make these exchanges all the more aggravated,

and of course render the men all the more silly.

But while the two husbands made a good job, in

their different ways, of being flummoxed, then violently jealous, then

positively explosive, it was the elegant performance of Richard Terry as

the much maligned and attractively benevolent Maurice Duclos that really

gave the edge to this final scene. His refined manner, tender treatment

of both women and understanding outlook innocent of all presumption,

made this small role the catalyst not for disaster, but for

reconciliation.

So – a play of much wit and levity, variety, and

a production full of invention, wry humour and amid the human

explosions, riddled with audience guffaws. Great fun. To 04-11-16

Roderic Dunnett

26-10-16

|